My second example is the cover of the very first issue from 1906 of renowned anarchist Emma Goldman’s journal Mother Earth. At a verdant tree stands a young man and woman, maybe Ask and Embla. At the roots of the tree lays the fetters that they have just liberated themselves from. The man salutes the rising sun. They are both naked and the era seems to be simultaneously before the birth of civilisation and after its termination.

Despite the fact that Walter Crane now and then played with baccantic motives and portrayed ludic games out in the wild, the more carnal aspects of the thiasos were alien to the nature of his art. Likewise, the humans on this cover (by an unknown artist) lack any sense of sinfulness. Yet, the cover image, with the erected tree between the seperated lands, easily opens up for interpretations of a sexual sort. In any case, some kind of emancipated, physical senusalism is cherished. Reinforcing these arcadian qualities is the fact that whilst Crane maintained a hierarchical order, with the tree in the middle of the image, the visual “movement” on the cover is rather horizental: the glance of the viewers drift away from tree and mankind. The tree trunk may be pleasant to lean against, but it is the distant rising sun – and the utopian land its brings with it – that is the true centre of the world.

Despite the fact that Walter Crane now and then played with baccantic motives and portrayed ludic games out in the wild, the more carnal aspects of the thiasos were alien to the nature of his art. Likewise, the humans on this cover (by an unknown artist) lack any sense of sinfulness. Yet, the cover image, with the erected tree between the seperated lands, easily opens up for interpretations of a sexual sort. In any case, some kind of emancipated, physical senusalism is cherished. Reinforcing these arcadian qualities is the fact that whilst Crane maintained a hierarchical order, with the tree in the middle of the image, the visual “movement” on the cover is rather horizental: the glance of the viewers drift away from tree and mankind. The tree trunk may be pleasant to lean against, but it is the distant rising sun – and the utopian land its brings with it – that is the true centre of the world.

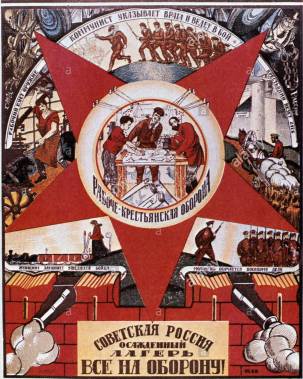

courtyards – has in the poster been substituted for a

courtyards – has in the poster been substituted for a

I would like to draw attention to a detail on a medallion deigned by Sergey Chekhonin (Tchehonine), from 1918.* On Chekhonin’s work of art an able-bodied female and a ditto male are depicted. The female stands before a cropland. She is carrying a sickle and a spade and so represents farmers. The male stands before a factory. He is holding a sledgehammer in his right hand, thereby seems to represent (despite Chekhonin’s choice of a non-factory tool as symbol) industrial workers. Behind him, on the ground, rests a parcel, perhaps with goods from his workplace. In his left hand – and it is this detail I found surprising – he carries a

I would like to draw attention to a detail on a medallion deigned by Sergey Chekhonin (Tchehonine), from 1918.* On Chekhonin’s work of art an able-bodied female and a ditto male are depicted. The female stands before a cropland. She is carrying a sickle and a spade and so represents farmers. The male stands before a factory. He is holding a sledgehammer in his right hand, thereby seems to represent (despite Chekhonin’s choice of a non-factory tool as symbol) industrial workers. Behind him, on the ground, rests a parcel, perhaps with goods from his workplace. In his left hand – and it is this detail I found surprising – he carries a  From the late 19th and early 20th century, we spot the caduceus – or Mercury himself, or symbols associated with him (especially his winged helmet) – on trade union banners and emblems. In Sweden and Denmark – and certainly in the countries that harboured workers’ movements that influenced the culture of these small countries, Germany and Britain above all – the banners and emblems decorated with this symbolism belong to unions that organized personnel working in shops, offices and akin workplaces.** This is hardly surprising since Mercury (Hermes) famously is, among other things, the god of commerce.

From the late 19th and early 20th century, we spot the caduceus – or Mercury himself, or symbols associated with him (especially his winged helmet) – on trade union banners and emblems. In Sweden and Denmark – and certainly in the countries that harboured workers’ movements that influenced the culture of these small countries, Germany and Britain above all – the banners and emblems decorated with this symbolism belong to unions that organized personnel working in shops, offices and akin workplaces.** This is hardly surprising since Mercury (Hermes) famously is, among other things, the god of commerce.

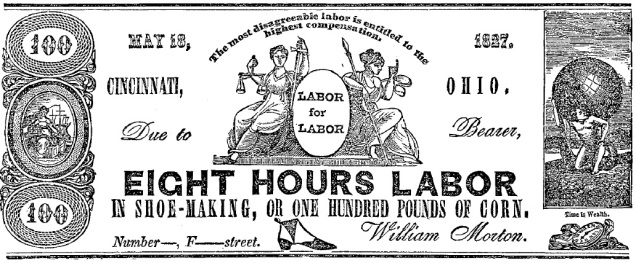

The very first notes ever to be printed and circulated in a socialist realm is probably

The very first notes ever to be printed and circulated in a socialist realm is probably  Having Google-translated three Russian texts that Roland Boer (

Having Google-translated three Russian texts that Roland Boer (